Global Warming Science - www.appinsys.com/GlobalWarming

Sahel, Africa

[last update: 2010/06/13]

|

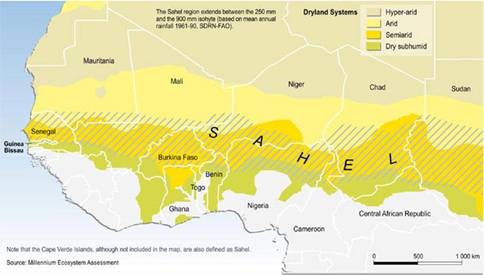

The Sahel region is in sub-Saharan Africa and is a transition zone between the arid Sahara desert to the north and the tropical green forest to the south, covering a surface area of 5.7 million Km2 with a population of about 60 million inhabitants. The vegetation In the Sahel region is composed of mainly stunted and scattered trees, shrubs, bushes and grasses. The Sahel is often the focus of U.N. and NGO aid due to the extreme poverty and recurring droughts.

In West Africa the Sahel is also a geopolitical entity -- the Permanent Interstates Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS) was formed in 1973 by Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Chad, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Senegal. More than half the working-age population in the Sahel is engaged in or dependent on agriculture and is responsible for more than 40 percent of the region’s collective gross domestic product (GDP). According to CILSS, the population is growing very quickly -- there will be 100 million people in the region by 2020 and 200 million by 2050 – almost four times the current population. [http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=78514]

|

|

Temperature

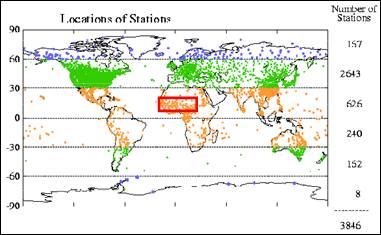

There are very few temperature long-term stations in the Sahel area.

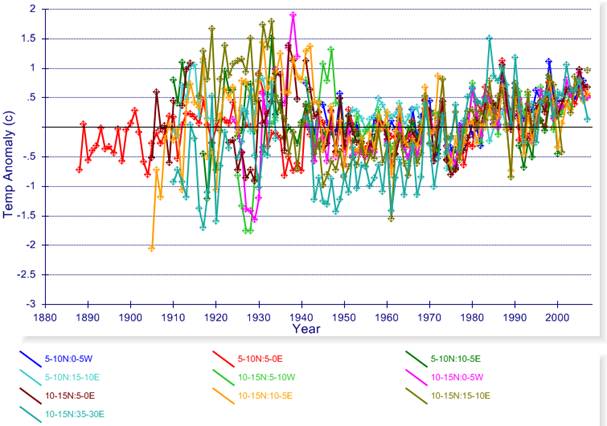

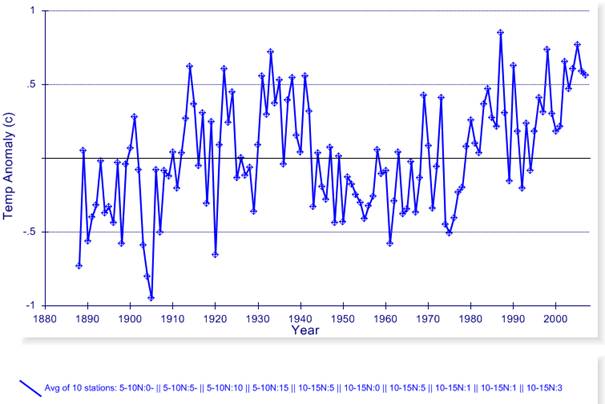

The following two figures show the available long term temperature anomaly data from the Hadley Climatic Research Unit (HadCRU) 5x5 degree gridded data [www.cru.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/temperature/] plotted at http://www.appinsys.com/GlobalWarming/climate.aspx. The top figure shows the temperature anomaly plots for the individual grids, while the lower figure shows the same 10 grids averaged. Recent warming has on average just begun to exceed the warming of the 1930s. (There are no long-term continuous temperature stations in the NOAA Global Historical Climate Network database for the Sahel.)

The following figure compares the HadCRU temperature anomaly data shown above with the IPCC AR4 Ch.9 report climate models for the Sahel. The blue band shows the climate models with only natural forcings, while the pink band shows the models including anthropogenic CO2. The HadCRU historical temperature anomalies are shown as the thin blue line. Although the models indicate that anthropogenic warming started in the 1970s, the historical temperature since then is mostly below the pink band.

Comparison of IPCC AR4 Models with HadCRU Temperature Data

|

|

Precipitation

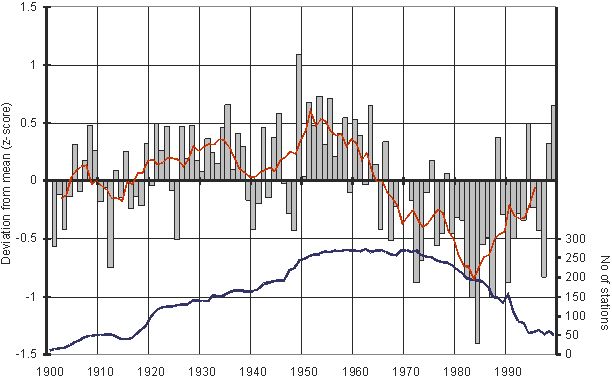

The Sahel region had a long period of declining rainfall from the early 1950s to the 1980s, with increasing rainfall since 1985, as shown in the following figure showing deviation from mean precipitation for 1900 to 2000 [http://www.eoearth.org/article/Greening_of_the_Sahel].

Sahel Rainfall and number of stations providing data

The UN IPCC AR4 Ch.9 report states that most “coupled climate models with prescribed anthropogenic forcing do not simulate significant trends in Sahel rainfall over the 1950 to 1999 period” and “recent research indicates that changes in SSTs are probably the dominant influence on rainfall in the Sahel, although land use changes possibly also contribute” [http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch09.pdf]. In other words the climate models do not successfully duplicate the rainfall trend.

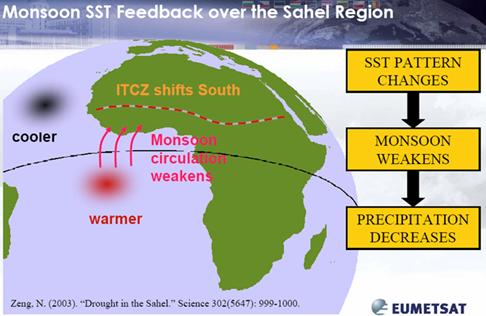

Rainfall in the Sahel is seasonal based on the position of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). “The onset stage of the summer monsoon over West Africa is linked to an abrupt latitudinal shift of the ITCZ from a quasi-stationary location at 5°N in May–June to another quasi-stationary location at 10°N in July–August.” [http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/1520-0442%282003%29016%3C3407%3ATWAMDP%3E2.0.CO%3B2]

The relative sea surface temperatures (SST) can affect the annual ITCZ position:

http://lpvs.gsfc.nasa.gov/LPV_meetings/Beijing09/Govaerts.pdf

|

|

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)

The following figure shows the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO -- see www.appinsys.com/GlobalWarming/AMO.htm for more details on this oceanic oscillation).

The following figure overlays the AMO (magenta) and the rainfall (brown) shown previously under precipitation. It shows a definite correlation between the AMO and Sahel rainfall for the last 60 years.

Comparison of Rainfall and AMO

The following figure is from a study (“Impact of Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillations on India/Sahel Rainfall and Atlantic Hurricanes” - Zhang and Delwoth, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 33, 2006 [http://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/reference/bibliography/2006/roz0603.pdf]) showing the correspondence between the AMO (top) and the Sahel rainfall (bottom).

|

|

Deforestation

“CHAD: Panic, outcry at government charcoal ban” [http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=82436]: “Government officials said the charcoal ban was part of an effort to halt tree-cutting for fuel, which they said was essential to fight desertification. The government has attempted to block tree-cutting in the past but has severely cracked down in recent weeks, aid workers and residents told IRIN. “Chadians must find other ways to cook and forget about charcoal and wood as fuel,” Environment Minister Ali Souleyman Dabye recently told the media in N’djamena. “Cooking is of course a fundamental necessity for every household. On the other hand...with climate change every citizen must protect his environment.”

“However, blaming the ‘environmental crisis’ on low and irregular annual rainfall alone would amount to a sheer oversimplification and misunderstanding of the Sahelian dynamics. Climate is nothing but one element in a complex combination of processes that has made agriculture and livestock farming highly unproductive. Over the last half century, the combined effects of population growth, land degradation (deforestation, continuous cropping and overgrazing), reduced and erratic rainfall, lack of coherent environmental policies and misplaced development priorities, have contributed to transform a large proportion of the Sahel into barren land, resulting in the deterioration of the soil and water resources.” [http://www.unep.org/Themes/Freshwater/Documents/pdf/ClimateChangeSahelCombine.pdf] “The region is marked by high rates of deforestation, soil degradation, erosion and population growth, as well as by weak political and private sector institutions. … In fiscal year 2005, the U.S. Government, through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), has provided more than $122 million from the American people to programs that will help improve lives in the Sahel” [http://www.usaid.gov/press/factsheets/2005/fs050810.html]

“the most important cause of environmental degradation in the ASAL [arid and semi-arid lands] is the rapidly increasing human and animal population pressure, leading to overexploitation of and intensified stresses on the natural resources. … This problem of rapidly increasing population pressures on the fragile and vulnerable soils of Africa's dryland regions translates into overexploitation of water, land, forest and pasture resources through overcultivation, overgrazing, deforestation and poor irrigation practices. The resulting erosion and degradation of productive lands has led to food insecurity. … The exploitation of woodland resources around towns is leading to deforestation, increased soil erosion and sand dune encroachment. The rapidly growing demand for charcoal among urban populations is leading to severe desertification within a 40-50km radius of many large urban centres in eastern Africa and the Sahel. According to some reports, rising charcoal consumption in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, has caused the area of charcoal production to shift to the south by an average of 15-20km a year. The charcoal supplies for Khartoum now come from as far as 400km away. The incidence of deforestation resulting from fuelwood requirements and in association with subsistence and commercial farming is spreading throughout the Sudano-Sahel region. The impact of drought, together with steadily increasing population pressure on arable land, has led subsistence farmers to move out of marginal or depleted lands to extend cultivation into forested areas or fragile river basins and mountain zones. The encroachment of cultivation on these vulnerable lands has led to loss of biodiversity and accelerated soil erosion, making the people even more vulnerable to future droughts.” [http://www.tiempocyberclimate.org/portal/archive/issue08/t8art1.htm]

|

|

Vegetation and Agriculture

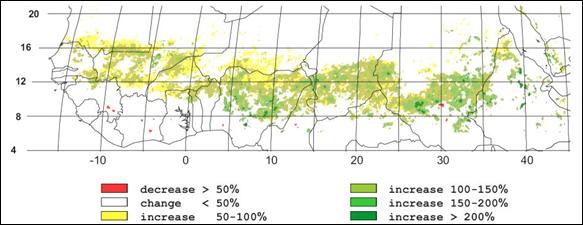

Since the 1980s, the vegetation has been increasing in the Sahel. The following figure shows the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), showing substantial increases throughout most of the region. [http://www.eoearth.org/article/Greening_of_the_Sahel].

NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) 1982 - 1999

The following figure shows observed NDVI trend for the Sahel from another study. [http://www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/5/3045/2008/bgd-5-3045-2008.pdf]

Even the normally alarmist National Geographic admits it: “Sahara Desert Greening Due to Climate Change?”, July 2009 [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/07/090731-green-sahara.html]: “Desertification, drought, and despair—that's what global warming has in store for much of Africa. Or so we hear. Emerging evidence is painting a very different scenario, one in which rising temperatures could benefit millions of Africans in the driest parts of the continent. Scientists are now seeing signals that the Sahara desert and surrounding regions are greening due to increasing rainfall. … Images taken between 1982 and 2002 revealed extensive regreening throughout the Sahel, according to a new study in the journal Biogeosciences. … "Now you have people grazing their camels in areas which may not have been used for hundreds or even thousands of years. You see birds, ostriches, gazelles coming back, even sorts of amphibians coming back," he said. "The trend has continued for more than 20 years. It is indisputable."”

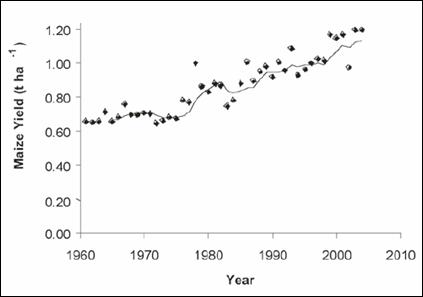

A United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) report in 2006 (“Climate Change and Variability in the Sahel Region: Impacts and Adaptation Strategies in the Agricultural Sector”) [http://www.unep.org/Themes/Freshwater/Documents/pdf/ClimateChangeSahelCombine.pdf] states: “The increase in aggregate food production (per capita food production has been declining due to rapid population growth), which has been observed in the Sahel and many other parts of sub-Saharan Africa since the early 1980s, has primarily been driven by the continued expansion of the cultivated areas. In the same time, yields of the major cereal crops have been stagnating, with the exception of maize, which has followed a relatively steady progression since the mid-1970s.”

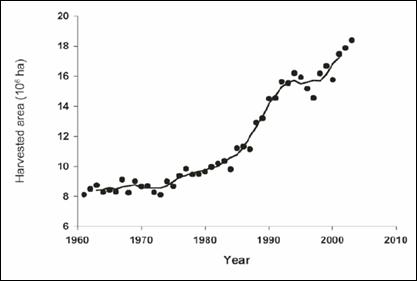

The World Bank World Development Report “Agriculture for Development” 2008 [www.worldbank.org/WDR2008] states: “Sub-Saharan African countries account for 89 percent of the rural population in agriculture-based countries … real agricultural GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa has accelerated from 2.3 percent per year in the 1980s, to 3.3 percent in the 1990s, and to 3.8 percent per year between 2000 and 2005. Rural poverty has started to decline in 10 of 13 countries analyzed over the 1990–2005 period.” The following figures are from the above UNEP report, showing total harvested cereal area and average maize yield from 1961 to 2004. Total area harvested has more than doubled in the last 30 years as has the average maize yield. Keep in mind that UN Secretary-General's Special Adviser on conflict, Jan Egeland refers to the Sahel as “experiencing the worst effects of climate change in the world … environmental degradation and climate change is killing life here; how humanity is struggling under climate change.” [http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/IRIN/d676d409fa4fdd336804cd367d59ea65.htm] Apparently he didn’t read the UNEP report or look at actual rainfall data. “Global warming” has increased the rainfall and the food supply in the Sahel – but rapid population growth overwhelms the increase. Egeland is playing the political game of trying to blame environmental degradation due to overpopulation on western countries for causing “climate change”.

Total area of cereals harvested in the Sahel since 1961

Average maize yield for the nine Sahel (CILSS) member countries since 1961

|

|

Inland Niger Delta, Mali

In his 2008 tour of the Sahel, UN Secretary-General's Special Adviser on conflict, Jan Egeland toured a Lake Faguibine restoration project in Mali and said: “When all the world's leaders are there [in Copenhagen] we must ask if we are really going to let life-saving projects like this, which are directly related to climate change, go unfunded. That would really be a moral failure; if climate change projects that already exist to help affected people go unfunded by those industrialised nations that caused climate change!” [http://allafrica.com/stories/200806050699.html].

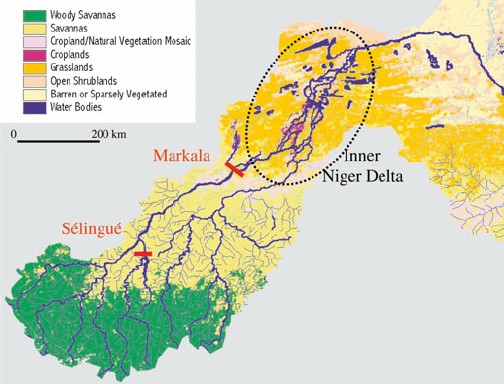

Lake Faguibine is a basin with no continuous inlet or outlet – it is periodically filled by flooding from high levels in the Niger River. A UNEP report states that Lake Faguibine “is connected to the main Niger River by two long (65 and 105 km) and tortuous channels that eventually join and carry the water over another 20 km to the first depression, Lake Télé. In favourable years the water can spill over into the main Lake Faguibine, some 60 km further north.” [http://www.unep.org/pdf/Lake-Faguibine.pdf] This lake is in adjacent to an area of Mali called the Niger Inland Delta – “a complex combination of river channels, lakes, swamps, and occasional areas of higher elevation” [http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=8249].

The same UNEP report states: “Lake Faguibine dried out completely in 1914 and 1924, again in 1944 and has been at very low levels since the mid 1970s. The series of good floods from 1924 to 1930 and from 1951 to 1955 completely filled the lake. This indicates that, for complete filling, the water balance of the Lake … needs to be positive for a series of consecutive years. Such series of high flood years have not occurred since the 1970s. However, from a human livelihood perspective, complete filling of the Lake is not its most desirable state as the best recession agriculture soils and high quality flood-dependent pasture are situated in the lowest parts of the Lake. The annual flooding and drying of these areas is perceived locally as the ideal state.”

“Mali is highly dependent on wood for its fuel needs. Over 90% of energy needs are met from primary sources such as wood and charcoal. However, Mali has never had extensive forest cover. Deforestation for the purposes of agriculture, fuel and building materials has denuded vast areas of Mali. Livestock grazing then slows the ability of the trees to regenerate. The lack of trees contributes to desertification.” [www.oxfam.org.uk/coolplanet/ontheline/explore/journey/mali/downloads/malreport.doc]

“The use of fire to manage agricultural land is one of the leading causes of land degradation; an estimated 14.5 million hectares of pasture are burned each year, equivalent to 17 per cent of the country“ [http://www.unep.org/pdf/Atlas_Mali.pdf]

The following figure shows a map of the inland delta with Lake Faguibine being the long narrow triangular shaped lake near the top of the dotted oval [http://www.waterfoodecosystems.nl/?page=1918]

The Niger River level feeding the inland delta and thus Lake Faguibine is dependent on the releases from the Markala dam. “Years with a peak discharge below 4000 m3/s occurred only twice between 1900 and 1980, but it has rarely been above this level during the last 20 years. This decrease is partly due to a reduced rainfall in the catchment area of the Niger, but can also be attributed to two dams in the river, upstream of the Inner Delta. At the Markala dam, an amount of 2.5 km3 water is taken each year since 1950 to irrigate 40.000 ha.” [http://www.waterfoodecosystems.nl/?page=1918]

The inland delta and its inhabitants are impacted, but new wetlands and agricultural areas have been created which replace them. “The impact of these dams in their own area is predominantly positive; especially for the Markala dam that had the sole purpose of creating new agricultural land. But also for the Selingué dam that had energy supply as a main purpose. Even some populations of waterbirds are now dependent on associated newly created wetlands. However the Inner Niger Delta and its 1 million inhabitants lose out completely. … Due to the Sélingué reservoir and the irrigation by the Office du Niger, the water level in the Inner Niger Delta has been lowered by 20 to 25 cm. As a result of the lower water levels the inundated area of the Inner Niger Delta has been decreased by 900 km2”. [http://www.prem-online.org/archive/11/doc/Wetlands%20Upper%20Niger%20english.pdf]

Thus it appears UN Secretary-General's Special Adviser on conflict, Jan Egeland, is either ignorant of the actual situation at Lake Faguibine or (more likely) is purposefully distorting it for the UN’s political goals.

|

|

Sahel’s Connection to Atlantic Hurricanes

Atlantic hurricanes reaching the eastern United States begin as thunderstorm clusters in the Sahel. Rainfall from this region comes from mesoscale convective systems, or strong clusters of showers and thunderstorms that produce tropical rainfalls. These eventually move into the waters of the Eastern Atlantic, and become the one hundred or so tropical waves that develop in the Atlantic Basin each hurricane season. On average, about ten of these become named storms, of which about six become hurricanes with two becoming major hurricanes. [http://www.hurricaneville.com/sahel.html] In recent years rainfall in the Sahel region has been normal or above normal, a contributing factor to increased hurricanes (although sea surface temperature anomalies have a larger influence when they increase – see info on the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation).

The 1992 study “Long-Term Variations of Western Sahelian Monsoon Rainfall and Intense U.S. Landfalling Hurricanes” (Landsea, Gray, Mielke, Berry [http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/vari/index.html] states: “Variations of U.S. landfalling intense hurricane activity are shown to be strongly related to western Sahelian rainfall during the last 92 years. This association is strongest for the U.S. East Coast and is significant both for the Florida peninsula and t he upper Atlantic Coast.” The following figure compares hurricane strength tracks of landfalling intense hurricanes (category 3, 4, 5) along the U.S. coastline during the 23 wettest years in the Sahel (upper panel) and the 23 driest years in the Sahel (lower panel) since 1899. [http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/vari/fig5.html]

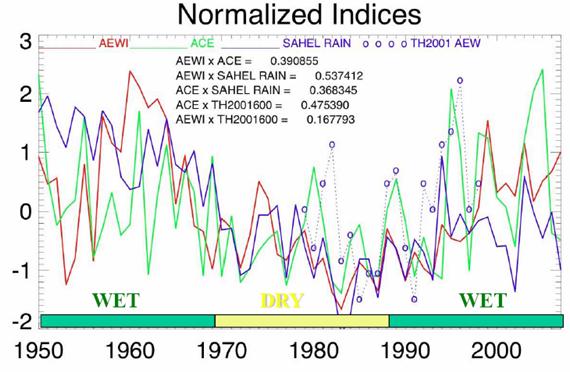

The following figure compares Sahel rainfall (purple) with the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE – green) indicating the correspondence between Sahel rainfall and Atlantic hurricanes. [http://www.ecu.edu/renci/floyd/slides/Floyd_B07_African-Waves.pdf]

|

|

|